Why People Compromise Quality And How Leaders Can Prevent Company Failure

“We pursued growth over the speed at which we were able to develop our people and our organization, and we should be sincerely mindful of that.” Akio Toyoda, 2010

In 2010, Toyota, the global symbol of quality and operational excellence, faced a crisis that exposed an unseen organisational weakness. While public attention centered on unintended acceleration and brake failures, the root causes of quality failures in its cars ran deeper: internal dynamics rewarded speed over safety, suppressed open communication, and ignored early warnings.

Toyota’s leader admitted that the pursuit of growth had led to vulnerabilities in its human systems and culture, especially those aspects that shaped how employees thought, communicated, and acted under pressure. For Toyota, a historically strong reputation for quality and efficiency masked a growing weakness: the organisation had become overly focused on manufacturing volume at the expense of sound decision-making and responsiveness to safety issues. Growth outpaced organisational readiness, and performance systems skewed away from long-term value, eroding its key competitive differentiator of product quality. Toyota mitigated the breakdown of trust with customers and reputational harm through an extensive response that returned the company to its usual equilibrium. It was, nevertheless, a period during which Toyota struggled to manage the fallout. Less mature firms have suffered much greater consequences from their quality failures.

Where Quality Failed: Five Corporate Case Studies

Here are five examples where people caused catastrophic corporate failures by compromising quality:

1. BP’s Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill. In 2010, the Deepwater Horizon explosion triggered the worst offshore oil spill in U.S. history. Investigators found that BP, Halliburton, and Transocean made repeated decisions that saved time and money but increased risk. Poor oil well design, inadequate testing, and weak safety protocols stemmed from a culture prioritizing cost-cutting over caution. The resulting $60+ billion in damages caused lasting reputational harm, which echoes today. BP remains vulnerable to takeover, with its share price almost half its pre-crisis level in 2010.

2. Carillion’s Cautionary Tale in Construction. Carillion’s downfall in 2018 began with greater scrutiny arising from being forced to fix eight cracked transfer beams at the Royal Liverpool Hospital. The firm subsequently collapsed after years of aggressive bidding and creative accounting. The company booked profits before projects were complete, masking poor performance. Auditors also failed to challenge inflated projections. Parliament later cited a “rotten corporate culture” amidst a relentless push for cash over sustainable quality in service delivery.

3. Volkswagen and “Dieselgate”. Volkswagen’s emission scandal revealed deliberate deception: vehicles were fitted with software that manipulated emissions readings during testing. In normal driving, emissions exceeded legal limits by up to 40 times. The company sacrificed regulatory compliance after an obsessive focus on becoming the largest global carmaker seeped into its operations. The scandal triggered fines, lawsuits, and significant brand damage. As with BP, VW’s share price has suffered ever since and remains less than half its pre-scandal level.

4. Boeing’s Safety Compromise. The 737 MAX crashes in 2018 and 2019 were traced to multiple failings, including design flaws, internal warnings that went unheeded, and a breakdown in transparency. Boeing’s cultural shift, from being engineering-led to becoming finance-driven, emphasized speed to market and cost control over aircraft quality. Subsequent failures, including a 2024 mid-air cabin plug detachment, show that serious issues persist.

5. Pacific Gas & Electric’s (PG&E) Wildfire Liability and Bankruptcy. California utility PG&E faced billions in liabilities from fires linked to faulty equipment and deferred maintenance. A cost-saving mindset arising from a strategy of “run to failure” delayed essential upgrades and inspections. In 2019, PG&E declared bankruptcy, highlighting the danger of postponing investments in critical infrastructure.

For all these high-profile, quality-related scandals, myriad investigations and reports have highlighted many facets of failure. Poor governance, bad incentives, warped decision-making, toxic organisational culture, ethical lapses, and inadequate management have all been cited. But is there an underlying causal factor that links them all?

The Core of Quality Problems: How Firms Manage Value

The starting point in assessing any significant quality failure should always consider how the organisation defines and manages value.

The underlying purpose of any firm can be found in its value motive. It’s the value motive that directly informs strategic decision-making, business planning, and the array of systems designed to drive the performance of the organisation and every individual within its whole system. It’s the value motive that also sets a key foundation for a company’s culture.

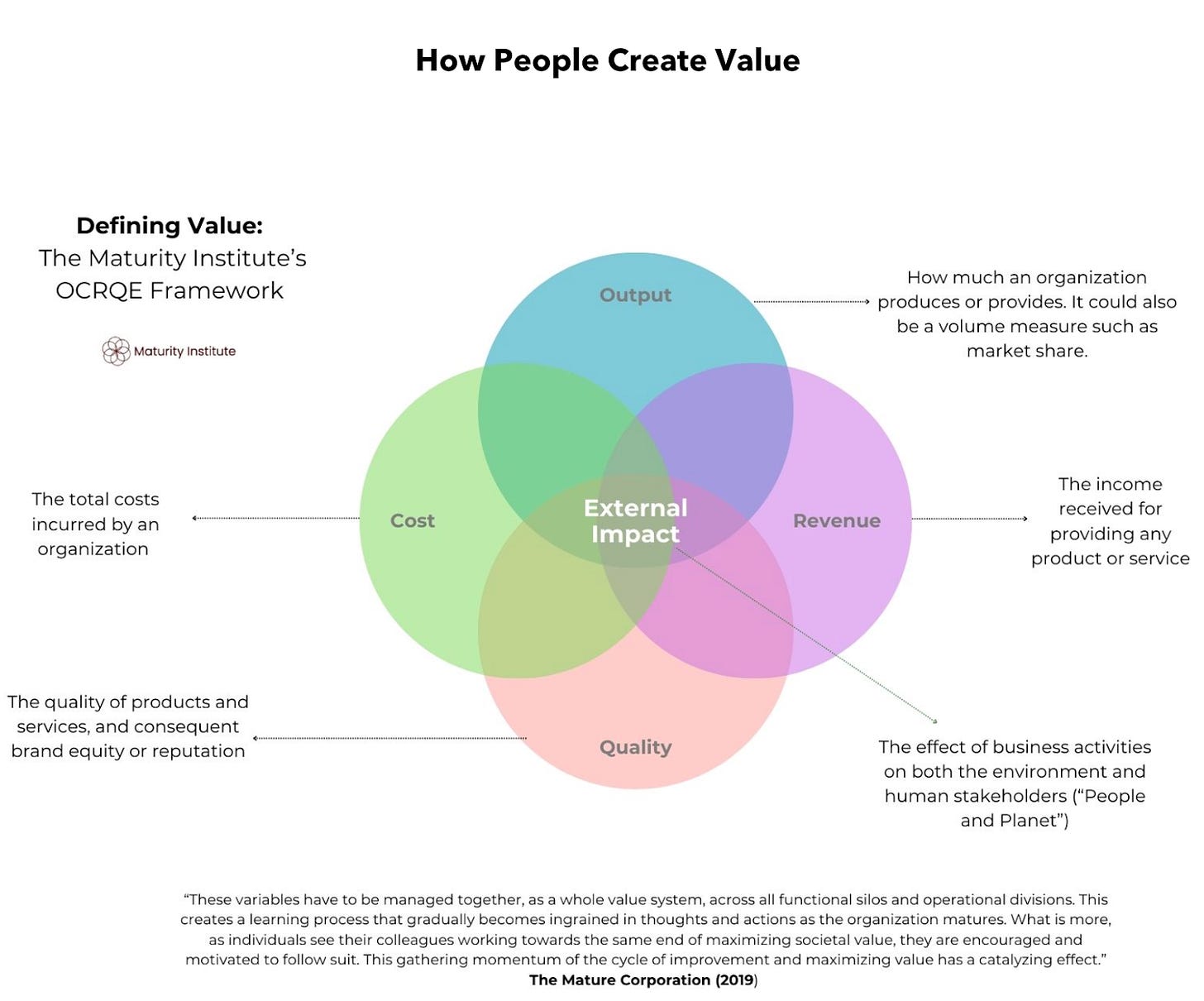

In the image below, the Maturity Institute’s (MI) OCRQE framework, value comprises a balanced system of five interrelated factors that apply to any organisation:

O = Output – What the organisation produces or provides (goods, services)

C = Cost – The full cost of producing that output

R = Revenue – The income or economic return generated from the output

Q = Quality – The standard or reliability of products and services produced or provided

E = Externalities / External Impact – The wider cost, impact, and consequences (positive or negative) for society, the environment, and stakeholders

In this form, value equates to growth and profitability (revenue minus cost), adjusted for quality and external impact. This ties directly into how MI defines a value motive founded on maximising Total Stakeholder Value (TSV), where a growing body of evidence now tells us that the most mature firms outperform financially (e.g, for shareholders) and for all their stakeholders, e.g., workers, customers, suppliers, and local communities. The evidence also tells us that mature firms carry less human risk and are inherently more stable.

Getting the Value Equation Right: Lessons from Mercadona

Mercadona’s staff are expected to create value by contributing to”Total Quality”, which prioritizes the satisfaction of their “bosses” (customers). This involves delivering high-quality products at competitive prices, creating a welcoming shopping environment, and ensuring excellent customer service. The workforce also contributes by operating efficiently, participating in co-innovation projects, improving impact, and helping maintain a positive and collaborative work environment.

The consequence of managing this model is that the firm’s performance metrics go beyond financials and integrate wider value factors. For example:

Customer quality and trust are measured by return rates, regular feedback, and repeat purchases

Employee engagement is tracked via retention, communication, training, and promotion rates

Supplier relationships are evaluated by contract length, innovation projects, and payment practices

Capital use is judged by reinvestment and efficiency ratios

Societal impact is assessed through environmental measures and community metrics

Mercadona’s value model has helped to ensure that its operations align with its purpose and continuously improve its performance across all stakeholder groups. By embedding quality and stakeholder value into its core systems, Mercadona has largely avoided serious quality compromises that have plagued competitors. Results? The company consistently holds the largest share of Spain’s grocery retail market and is the highest-grossing supermarket chain in Spain. It serves millions of customers weekly and is widely regarded as the preferred supermarket for Spanish households, according to consumer surveys. The quality of Mercadona makes it Spain’s supermarket leader.

Conclusion: Leadership Lessons in Sustaining Quality

1. Manage the full system of value. Move beyond financial performance by elevating quality, trust, and societal impact to leadership agendas.

2. Strengthen organisational immunity. Ensure the organisation has a total quality management system that encourages learning, escalates early warnings, and reinforces ethical decision-making.

3. Balance growth with capacity. Avoid stretching people, processes, or systems beyond their ability to sustain excellence.

4. Align performance and incentives with long-term, stakeholder value. Manage and reward behaviours that support enduring quality, not just quarterly and annual earnings.

5. Measure what matters. Use metrics that reflect desirable stakeholder outcomes, e.g., well-being; not just output, revenue, and efficiency.

Quality should be fused into every business model and leadership mindset to become embedded in culture, strategy, and decision-making. Organisations that understand this not only avoid crisis; they earn the enduring trust of those they serve.